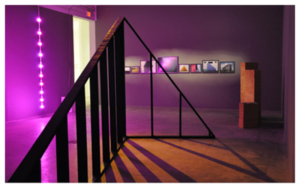

Nicole Cherubini, a New York-based sculptor with a strong commitment to ceramics, recently opened 500, a solo exhibition at PAMM.

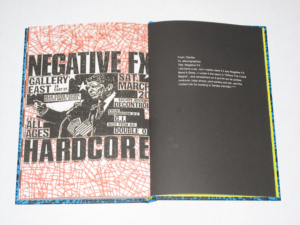

Source 2012 [NAME] Publications "Source, with transcendental passages of analogy and allegory is an invitation to a reality of Americana, slightly

[NAME] Publications was founded in 2008 by Gean Moreno, a Miami-based artist and writer whose own recent works in the

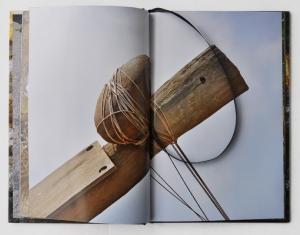

2011 Published by Gallery Diet With an essay by Ruba Katrib Subjecting the landscape to a critique, as an art

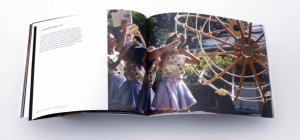

I Saw Three Cities, Felecia Chizuko Carlisle’s solo exhibition at Dorsch Gallery, takes its title and leitmotifs from a painting

Corin Hewitt’s practice fuses photography, sculpture and the sort of critical inquiry into the classification of natural and cultural

A few weeks ago nearly a hundred academics, artists, educators and critics descended upon the University of North Carolina’s Asheville