A few weeks ago nearly a hundred academics, artists, educators and critics descended upon the University of North Carolina’s Asheville campus for an on-site conference examining the legacy of Black Mountain College, the first since the institution’s closure in 1957. Founded in 1933 by a group of academics and students eager to practice theories of progressive education, Black Mountain College held the arts and creative inquiry in high esteem, hosting John Cage, Merce Cuningham and Buckminster Fuller at the isolated Appalachian campus early in their careers. Faculty-owned, Black Mountain College offered an approach to higher education radically different than typical colleges of its day. Students, faculty and staff lived communally, classes were open-format, and students developed their own courses of study. Students and faculty alike were committed to their experiment, although the college’s finances were always tenuous. Food was grown at the college farm, students maintained the campus themselves to save money, and faculty often worked without pay. The college ultimately ran out of funds in 1957, but its faculty and alumni went on to become major cultural contributors for the remainder of the 20th century.

Lee Hall porch. Photo courtesy North Carolina State Archives, Black Mountain College Papers.

The conference hosted such a comprehensive yet uneven array of panels and presentations that, moving from lecture to lecture, one got the feeling of strolling through a live-action mockumentary staged by Christopher Guest. A number of panels debated the legacy of BMC in arenas such as critique-based art education in California graduate programs, the queer community, practicing contemporary artists, and pottery education. A discussion heavy on the minutia of daily life at Black Mountain College (a tuna casserole dinner was served on the porch of Lee Hall some time in 1937) gave way to a debate about whether Cage’s first happenings at the Eden Lake campus were an early, atemporal instance of postmodernism. Eva Diaz from Pratt discussed the politics of geodesic domes in contemporary art, while the next presenter obliquely described a college he started in Pennsylvania before stumping for donations. Next to an indoor Bucky-ball playground situated under an idiosyncratic wall-sized public art adaptation of the School of Athens, a panel on Chance Operations saw three simultaneous presentations accompanied by prepared guitar, feedback pedals, and voice interjections.

iPhone photo of Chance Operations panel by Terry Berlier.

Bucky-balls and The School of Athens at UNC Asheville.

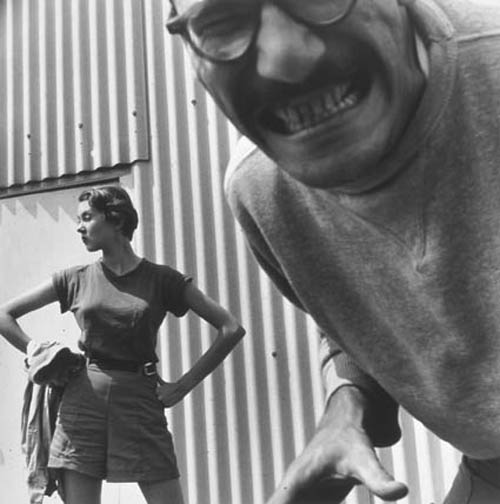

Buckminster Fuller at BMC.

BMC operated on a shoestring budget in the remote Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina from Great Depression until the McCarthy era of the mid-1950’s and was viewed with some apprehension by its Appalachian neighbors, compounding the community’s fiscally-imposed ethic of radical self-reliance. In contrast to the nearby Biltmore Mansion, a relic of the Gilded Age stuffed with valuable antiques and portraits by Seargent and Whistler of Anderson Cooper’s industrialist ancestors, the Vanderbilt clan, BMC’s Eden Lake campus consisted of a sprinkling of rustic lodges and one student-built modernist structure, the Studies Building, encircling a small reservoir. Along with small private studies for each student and faculty member, the Studies Building housed the studios of Nazi refugees Anni and Joseph Albers, whose influence on the teaching of art resonated far beyond BMC.

BMC students at looms.

Foosbal and lanyard supplies in Anni Albers’ former weaving studio.

On the day that conferees and former students toured the Eden Lake Campus, the second of the college’s homes on the outskirts of Black Mountain, the site was dominated by an enormous multi-parish Catholic church picnic. Eden Lake Campus is now Christian summer camp, and it appeared that a greater number of faithful were gathered that day than the entire sum of BMC’s student population during its 24 year lifetime. The tour itself functioned similarly to Cage’s first happening, Untitled Event, a radically fragmented event consisting of simultaneous presentations by poets, dancers, musicians and lecturers which was staged in the dining hall during the 1952 summer session. During the recent campus tour, the same dining hall was dominated by a BBQ sandwich line and homemade dessert tasting contest as a group of Black Mountain College enthusiasts cut a swath through the churchgoers. Today the Studies Building, still a striking Bauhaus form nestled in the rolling hills, doubles as an infirmary. The fabled basement pottery and weaving studios are still devoted to arts and crafts, while the lawn where Buckminster Fuller attempted to erect his Supine Dome and Merce Cunningham rehearsed with his first dance troupe was overtaken by a surprisingly ambitious running race for kindergartners.

Eden Lake Campus today.

One leaves the idyllically situated campuses with a sense that the college’s remoteness and the intensity of a life apart from the surrounding Appalachian communities and current events, yet radically together in an evolving community, contributed to its lasting legacy. At Black Mountain College, students and faculty had the time to develop bodies of work, thought, and practice imbued with a mindfulness that is difficult to attain in an infinitely more connected present.

Black Mountain College summer session.

Camper group portrait on infirmary door in the studies building.