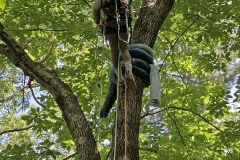

Treetopping (Blake’s Hitch, Ladder Tie, Limb Loop). Denim, cotton, poly-fil, installed in a red oak tree with the assistance of arborist Dylan Walsh at Unison Arts in New Paltz, NY as part of the exhibition Owning Earth.

The Arborist, a short story for Unison’s audio guide.

An arborist is standing at the base of a Quercus rubra, or red oak tree. The trunk of this individual grows tall and straight for twenty-five feet, and then it divides into two distinct halves, forming a high, strong crotch. Another twelve feet up on the right side, a sturdy limb arcs over the crotch. This is an ideal place for an arborist to work.

The arborist assesses the tree from the forest floor, circling its width before aiming a slingshot. The slingshot, with its V-shaped prongs perched atop a long pole, resembles the tree. The slingshot launches a weighted sack about the size and color of a Baltimore oriole, which carries a thinner cord called a throw line over the sturdy limb high in the tree. This thinner cord, in turn, pulls the climbing rope into place.

With the climbing rope securely tied to the base of a neighboring hickory, the arborist snaps into the harness and ascends a ladder made of air–stopping at the top of the trunk just below the crotch. The haunting chatter of a wood thrush wafts up from below, its etherial, flute-like call ending in an echoey metallic trill, like a pinprick that hit a nerve. The arborist embraces the trunk to judge its girth, and then, with arms embossed by the tree’s bark, pulls up the denim rope.

As the denim rope ascends from the forest floor, tied to the arborist’s climbing rope so that it doubles over on itself, it resembles the long, gangly legs of a cowgirl. She’s a tall drink of water.

The cowgirl’s legs stretch like taffy in the arborist’s hands, wrapping three times counter-clockwise around the trunk. The tail of the denim rope passes from below the other loops, gliding snugly between the tree and the rope coil. The working end obeys gravity, flopping limply towards the ground, and the tail passes over it and then under again in a half hitch. This is a limb loop, a foundational hold in shibari practice. It provides a point of tension, so that the rope bottom’s own body anchors the ties that bind.

More leg-rope ascends, and appears for a moment like a companion to the tree’s trunk–as if they might begin to walk together, and the tree could trundle away through the forest.

The arborist climbs a bit higher, resting a foot where the trunk meets the crotch. Just above the crotch, the leg-rope wends counter-clockwise around the thick thigh-limbs until it reaches the front again. The working end hitches over and around, through the middle of the V, cinching the back and front portions together. This bind, a ladder tie, is repeated twice more, each rung higher than the next. In rope play, this restraint binds the legs together so that they can be moved in unison. It must be applied with care and consent, both on the part of the tie-er and the one being tied.

The arborist ascends to just above the ladder tie, wrapping the denim rope four times around the high limb. The working end of the leg-rope swings back down, passes over the bottom portion, and snakes through the lower two turns. It squeezes up through the center, and hangs contentedly like a dog’s tongue on a hot summer’s day. This knot is Blake’s Hitch, the same one–with its special slide and friction–that transforms the arborist’s supple rope into an air ladder.

With this series of knots in place the arborist surveys the work. It is balanced, secure. Leg-limbs and tree limbs weave together. They vibrate with a sturdy sensuality. The arborist checks the climbing ropes, gives the Blake’s hitch a left-handed tug, lets the climbing rope slide slowly through the right hand’s glove, and descends, feet hitting the duff with a drum-thump at the base of the Quercus rubra, the red oak tree.